What’s a strangle option? If you’ve been learning about stock derivatives, you may have come across “strangles” as a term thrown around.

In this post, I’ll discuss:

- What is a strangle, and a numerical example.

- The risks associated with a strangle.

- What sorts of stocks are strangles meant for.

What’s A Strangle Option?

There are 2 types of strangle options: long strangles, and short strangles.

Let’s go through long strangles first.

Long Strangles

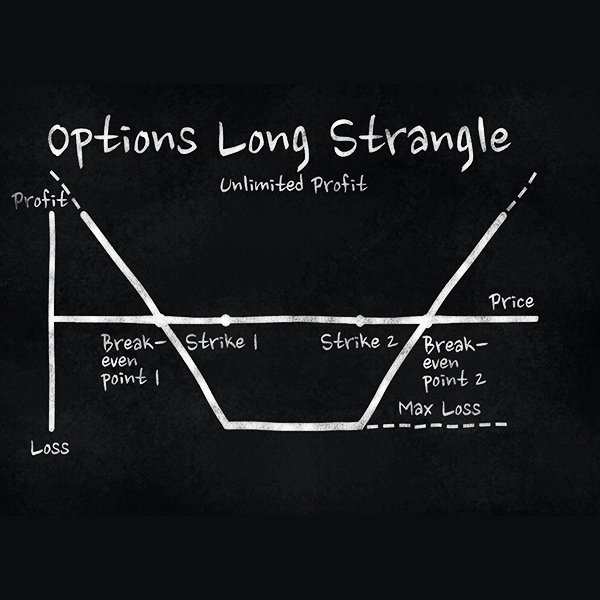

A long strangle simply put is buying both an out-of-the-money (OTM) call option, and an OTM put option with the same expiry date.

But…why? You either think the stock’s going up, or the stock’s going down. Why buy both?

Well, this is for precisely the case where the person doesn’t know if the stock will go up or down, but they just think the stock will be very volatile.

For example, stock $ABC is at $50, and you think after their earnings call, $ABC will move $10. This is because they’re engaged in some very risky plays and so any news would have an overreaction.

The problem is: you don’t know if it’s good news (i.e. going to $60) or bad news (i.e. going to $40).

So you hedge by buying 2 options:

- 1 $45 PUT, expiring the week after earnings.

- 1 $55 CALL, expiring the week after earnings.

- Together, this constitutes a strangle. Let’s say this strangle option costs you $300 in contract premiums.

Let’s take a look at a few scenarios so we can really understand how the numbers would work.

- $ABC skyrockets to $60/share and you net $200 with your strangle option play. Your PUT will expire worthless and your call will have a profit of $5/share. Recall 1 options contract = 100 shares. So, 100 shares * $5 profit/share = $500 gross profit total. Less the $300 in option premiums means you net $200.

- It plummets to $40/share and you net $200 also. Same reasoning, except your call will expire worthless while your put makes you money.

- $ABC rises to $58/share (or $42/share), and you breakeven. One or the other leg will always expire worthless. But your other leg will give you a gross profit of $300. Less the $300 in contract premiums cost and you’re breakeven.

- It goes to $56/share (or $44/share) and you lose $200. For example, you can redeem your ITM option for $100 (the other leg will expire worthless), but you paid $300 for the strangle option so you’re down $200.

- Anything between $45 and $55 and you’re looking at a total loss of $300. This is because both option legs in your strangle will expire worthless.

So why use this strategy?

Investors use this strategy if they speculate there’s volatility in the stock, and that the option premiums are underpriced given the projected volatility. And you can lose money if the stock remains fairly stable.

Keep in mind: the more expensive your straddle contract premium is, the more volatile the stock must be in order for you to reach your breakeven point.

Short Strangles

This is just the opposite of long strangles. So if you can conceptually imagine the above, but in opposite terms, then you’ll understand what this is.

But in case you don’t like doing mental gymnastics, short strangles is selling both an OTM call option and an OTM put with the same expirty date.

Why would you want to do a short strangle?

Just like how you’d do a long strangle if you perceive high volatility (compared to the options pricing), you might do a short strangle if you think there’s not going to be much volatility (compared to how expensive the options are).

How do you make money from a stock when it’s not volatile?

If you short an option, you’re selling an option to collect a premium for the contract without buying shares for it. In other words, if you sell an OTM contract, and it remains OTM, you keep the premium. If you sell an OTM contract and it becomes ITM, you need to buy the shares to cover it.

Let’s run through some examples.

- Say you sell to Bob 10 OTM calls at strike $30 for stock $XYZ. $XYZ is at $20. And you sell these calls at $0.45 per share. You collect $0.45 * 10 * 100 = $450.

- Scenario 1: The shares expire OTM, and you keep the $450 and you walk away.

- Scenario 2: The shares expire at $35, and now you have to cough up 10 * 100 shares at $35/share. You’ve made: $450 – $3500 (AKA you lost $3050).

- So if you sell a call option, you’re betting it won’t go up past a certain price by an expiry date. And if you sell a put option, you’re betting it won’t go down past a certain price by an expiry date.

- But what if you don’t think the stock will go up, or down? Then you can do a short strangle by selling both puts and calls.

Let’s go back to company $ABC where it is at $50. Only this time, you don’t think it’ll move after earnings. So you do a short strangle option where you sell a $45 put and a $55 call expiring a week after earnings. You collect $300 for the premiums.

Your rewards will be the opposite of the previous investor who went long on these positions. Let’s go through some examples again.

- The stock goes to $60/share. You lose $200. This is because you’ll keep your premium of $300. Except you have to fulfill the call side of the option. You buy the stock at $60/share for 100 shares, and you give the counterparty the right to buy it from you at $55/share. Thus, you’ll lose $5/share for 100 shares. Ergo, your profit is $300 (premium collected) – $5*100 = -$200.

- It goes to $56/share or $44/share and you gain $200. You keep your premiums ($300) but need to cough up a -$1/share (totaling -$100 because you did 1 strangle option contract) profit for the leg that expired ITM.

- It expires anywhere between $45 and $55 and you keep your entire premium.

Just think of short strangle options as just the opposite of long options. Because that’s what they are. The person executing the long option is the counterparty of the party executing the short option.

Risks Associated With Strangle Options

Here are the risks associated with long strangle options:

- Limited downside

- You can only lose the premium you paid for both the call and short options.

- Somewhat unlimited upside

- If stock goes up, then the “call” leg of your options pair can have unlimited gain. Your put will expire worthless. So while you’ll benefit from the unlimited upside of calls, your gains will be buffered due to your total loss of your put. But your put premium may be insignificant compared to your total gain if the underlying share price skyrockets.

- If stock goes down a lot, your call will expire worthless. Your upside is limited because puts’ upside is limited. Remember, the “puts” is on the short side, and the stock can only go down to $0. Your max profit here will be: (100 shares) * (Number of strangles you bought) * (How ITM on your put leg when your strangle expires) – (the strangle option’s premium).

And the risks for short strangles are opposite:

- Unlimited downside.

- Much like shorting a stock, you’re selling securities before you buy anything.

- If the price moves adversely, you’d still need to purchase the shares in order to cover your shorted options.

- If the share price goes down to 0, your downside is limited due to the fact that you’ll only need to cover your puts.

- However, the unlimited losses come from if the share prices skyrocket. In this case, you’ll need to buy shares at prohibitively expense prices just so someone else can redeem them for a lot cheaper.

- Limited upside.

- You maximum upside is going to be just the premiums of the 2 contracts you sold.

Should I Use Strangle Options?

One thing I like about strangles as compared to just regular “calls” or “puts” is it requires the maturity to realize you can’t predict the future.

With other options, you need to be almost over-confident on which direction the stock will go.

Personally, I’m a much bigger fan of long strangle options than short strangles due to risk profile. Here’s how I think short/longs play out:

- You’ll win more frequently with short strangles, but it takes just one “bad luck” event to bankrupt you. You can mitigate bankruptcy risk (a little bit) by closing out your positions as one of the legs go ITM. Your profit will just be (your premiums collected – new premiums on the long side to offset your shorts). This stop-loss isn’t bullet proof though because huge jumps or dips in the market after-hours could screw you anyway.

- You’ll almost never win with a long strangle, but it takes just one “good luck” event to retire you.

As with all financial derivatives, you should not invest any money you cannot afford to watch go into a large campfire. You’ll probably lose it. If you like making money instead, consider buying an S&P 500 ETF or something.

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks