In this post, I’ll be talking about an advanced option strategy: calendar spread options. I’ll walk you through:

- What are calendar spreads?

- An example of how a calendar spread works, with numbers. I’ll also point you to a convenient calculator tool (free) that you can use if you’d like to execute some of your own calendar spread option trades.

- Risks associated with calendar spreads.

- Whether or not you should use calendar spreads to trade.

Prerequisite: Before reading this article, you should know:

- What call options are.

- How shorting options work. In particular, I walk through some examples in this article talking about strangle options.

Without understanding how shorting options work, or how a basic call option works, the following will be a bit confusing. My recommendation if you don’t know options basics is to read the 2 articles I’ve linked above.

Calendar Spread Option: High-Level Definition

A calendar spread basically is an options strategy that exploits time, or theta, of options.

In particular, traders that use a calendar spread will be both shorting and longing an option with the same strike price.

Generally, you’d sell a near-term call as your short leg, and then buy a longer-term call for your long leg.

- NOTE: You can also short/long puts for your calendar spread, but in my examples I’ll just be using calls.

Using a call calendar spread option strategy is good for when the stock goes up a little bit, but not too much. This strategy can also be good you anticipate a stock to remain flat.

An Example Of A Calendar Spread

The current price of $TQQQ is at $127.48, down from an all-time high.

Let’s say, as an investor, you think the price will remain about the same, and perhaps go to ~$135 in about a month and a half.

Today is October 9th.

So what you could do is to sell a call option at $3.10 expiring October 29th, and then buy a call option expiring on November 26th for $6.8/share. Both options would have the strike price of $135.

- For this example, let’s say you shorted/longed one option contract on each side. Thus, you’ve sold an option at $3.10/share (i.e. $310 in proceeds). You’ve also bought one call option at $6.8/share (i.e. you spent $680 on the call option expiring November 26th).

- Thus, your total cost = $680 – $310 =$370.

If the price remains the flat at $127 until October 29th, you’ll keep the $3.10 you charged for the option. Therefore, you’ll keep your $310 in proceeds. Your November 26th call may have decreased in value, but it still has some value. Depending on how much the value has decayed, you can make or lose money here.

- In general, your long leg will be worth less than $6.8 now. This is because as time decays, there’s less “potential” for your stock to go to $135 by November 26th on October 29th when compared to October 9th.

- If your long option on October 29th is worth more than $3.7, you should be profitable. This is because your total cost to execute the calendar spread is $370. So, if you can liquidate your November 26th call at, say, $4, you’d earn $30 ($400 – $370).

- Conversely, you’ll lose money if your long option is worth less than $3.7 on Oct 29. If your November 26th calls drop to, say, $2, then you can only get $200 back for selling your calls. You can either: 1) sell it for a $170 loss immediately, or 2) gamble and hope the stock rises by November 26th so you can earn more money – there’s a strong possibility that the $2 option will drop to $0, however (i.e. expiring out-of-the-money).

If the price rose up to $140 by October 29th, your short leg would be in-the-money.

- You’d keep the $310 premium still. And if you didn’t have a corresponding long call option leg, you’ll lose $5/share in your contract, or $500, in order to cover the shares. Instead of this $310-$500 = $190 loss though, you can just close out your long call option to cover your short one (you owe 100 shares on the short leg but you’re entitled to 100 share on the long leg).

- You could also lose, or make money here. Your short leg is down $190, and you’ve paid $370 to execute the calendar spread. So, if you don’t count the value of your long call option, your calendar spread is down by $560. The good thing with a calendar spread option is this: if your short leg is ITM and you have to pay up, your long leg is also ITM. As there’s still time before your long call option expires, the option should have appreciated in value. In our specific case, you know that your long call is worth at least $6.8. Thus, you’d profit at least $680 – $560 = $120.

- This is the magic of calendar spread option. Your long leg insures against unlimited losses you’d normally have by selling naked calls. At the same time, you can even make a profit even if your short leg loses. The bad thing about calendar spreads is that your upside is limited. If you go too deep ITM, you’ll lose money instead.

- Suppose $TQQQ went to $500 instead on October 29. Both options would be pretty much the same in cost. The November option wouldn’t be much more valuable than the October option because it’s very unlikely that TQQQ would drop back to the strike of $135 by then. In that case, you’d have to close your calendar spread option, and have the long leg cover the short leg. You’d lose your net debit in this case (i.e. the $680 you paid for the long leg – $310 you got from selling the short leg = $370 loss).

Thus, with calendar spreads you want the price to either remain the same, or go up slightly. You’ll lose money if the stock goes up too much, or if the stock tanks (i.e. your long call leg also goes to 0).

Your best case scenario is generally going to be if the option expires right at the money. In this case, if market close on October 29th, $TQQQ reaches $135, you’re in the best position. This is because:

- You’ll keep the $310 from the sale of the short leg.

- The longer leg still has a month before expiry. And since the underlying stock has increased in value, you’ll no doubt make a profit on the longer leg as well.

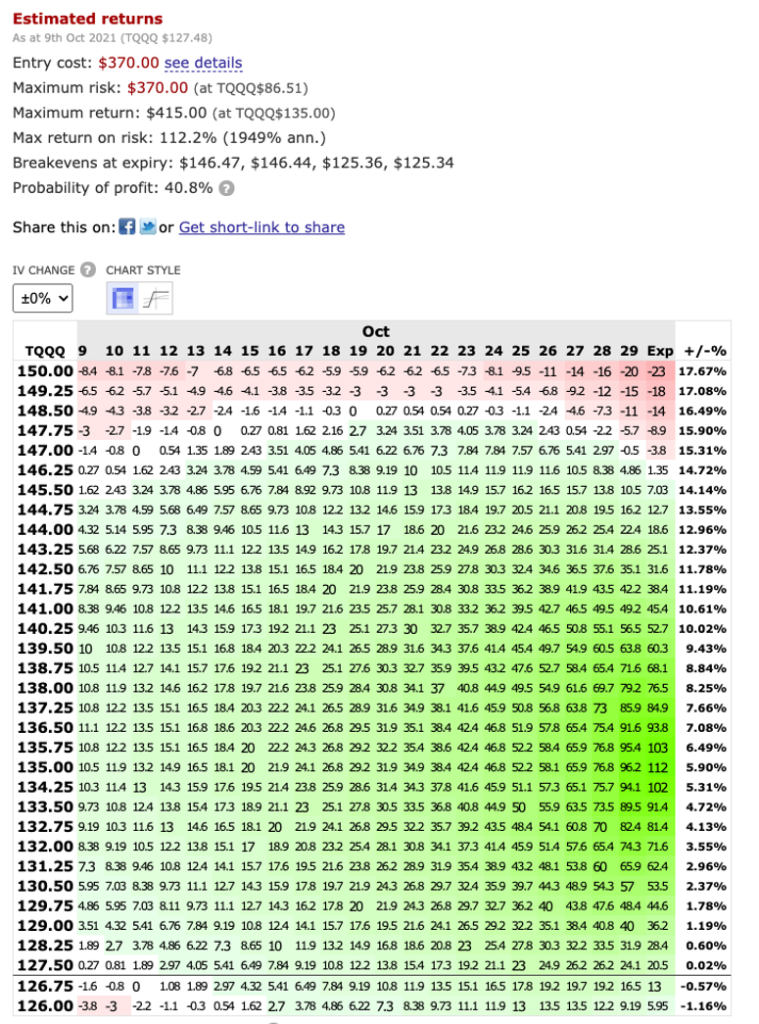

These 3 scenarios described above are reflected in the table below.

The x-axis is the date at which you close your calendar spread option. The y-axis is the underlying ($TQQQ) stock price. The value in the chart is how much % you’re making if you were to close out your position at the given date (x-axis) when the stock is at a certain price (y-axis).

If you’d like to use the same tool to estimate your returns on a calendar spread strategy, simply go to this link here. Keep in mind that the chart above is only an estimate (read below to see why).

Not An Easy Strategy To Execute

As you can see, this is pretty complicated and unlike single-leg options, calendar spreads are a bit unpredictable as far as your losses/gains goes.

Depending on the volatility of the underlying stock, the above chart is just a “best guess” estimate of what your profits would actually be if you were to close your position out at those dates/prices. It could be more, or it could be less depending 1) on how much the volatility changes over the course of the x-axis dates and 2) when the volatility changes happen.

This makes the calendar spread option strategy hard to execute, because your returns can’t be calculated with 100% accuracy, even if you knew in advance what the stock price would be at what time.

Though to be fair, nobody knows what return they’ll get because nobody knows what price a stock would be at a specific date.

If you knew in advance exactly what price the stock would be at what date, your best bet is just to do insider trading instead of calendar spreads.

Risks With The Calendar Spread Option Strategy

Your maximum downside is what you spent executing the 2 legs of the calendar spread. This is just the net debit (your cost for the long call option minus your proceeds from selling the short option). Thus, your downside is limited.

Your max profit is unlimited (with a caveat below) if you’re doing calendar spreads on calls. Your gains could be limited in the following scenario:

- Your short options leg expire worthless. AND

- In between the expiry date of your short leg and your long leg, the underlying stock skyrockets.

Caveat: Keep in mind that if the stock skyrockets before your short options leg expire, you’d incur maximum downside. This is because you’ll need to now cover your deep ITM short leg with your long leg.

Thus, this ‘unlimited gain’ scenario is fairly unlikely to happen because you’ll need to predict where the stock price would be at 2 different points in time. Guessing where the stock would be at expiry is hard enough already. To have the unlimited gains scenario you’d have to be able to do that twice. In one trade.

In general, things are ‘most favorable’ if the prices increase towards your short leg’s strike price, but never quite reaching it at the time of the short leg expiry.

- You get to collect the premium for selling the short option.

- Your longer leg option should also increase in price due to the volatility and delta from price increase.

- Side note: “Delta” refers to one of the options greeks. Delta refers to the change in option price as compared to the underlying stock price. For example, if a stock goes up by $1 and the option’s pricing goes up by 36 cents, then we’d say the “delta” of the option is .36. Another example: something that’s very deep in-the-money would have a delta close to 1. This is due to there being almost no chance that the underlying stock will ever cross the strike price. Thus, a dollar increase/decrease in stock price corresponds to a dollar increase/decrease in the option.

So…Should I Do This Or Not?

The first and probably the most important thing to know for the calendar spread option strategy is that the taxes are complicated.

For example, it’s not clear from my research if this calendar spread will automatically trigger a wash sale. The implications of this is either:

- If not a wash sale: You’ll be taxed on your gains/losses as normal (i.e. short-term gains/losses). OR

- If you’re reporting your calendar spreads as a wash sale: You must report capital gains. Your capital losses will not be counted. That is, you’ll be taxed on your calendar spread gains. But if you lose money on your spreads, you will not be able to use the losses to offset your other gains.

The wash sale makes this strategy really tricky because it creates an enormous headwind. You’ll need to win substantially more as a breakeven when compared to not having to do a wash sale.

If you’re going to pursue using calendar spread option as a strategy, please consult your accountant well-versed in advanced options strategies!

I say this is an advanced strategy because not only is the taxes complicated, but the options itself is complicated as well. From the above, you now know that:

- You make money when the stock stays flat, or has a slight increase.

- You lose money if the stock increases drastically, forcing you to cover your short leg with your long leg. You also lose money if the stock falls too much, because the premium you collected in your short leg won’t cover the value lost in the long leg.

- You can only at best estimate your profit/losses, but you can’t know for sure ahead of time. This further adds to the strategy’s complications.

Even in gambling, you know how much you’ll win or lose based on the rules of the game. Here, even if you know stock $ABC will reach a price of $35 on a specific date, you can only estimate how much money you’ll make (or lose). You can make some predictions on your gains/losses based on the stock’s implied volatility and Black-Scholes pricing – but those are only estimates, and can be wildly inaccurate if the market does something unexpected.

Not knowing even what you’d stand to gain is risky. But the one good thing about calendar spreads vs. say, just selling naked calls, is that you know your losses are limited to your net debit. Knowing your max loss is arguably the most important part. Thus, despite all the complications above, the calendar spread could be a viable strategy for people who:

- Are OK not knowing exactly how much money they’d gain from a position.

- Values the importance of limited losses vs. maximum gains.

- Know how to navigate the complex tax issues associated with this strategy.

- Have traded options a fair bit before and are comfortable with both the volatility and the complex tax implications of derivatives.

And even then, I’d probably not recommend calendar spread options because I feel like it’s strictly better not to complicate your taxes. If you think the stock will go up to, say, a price of $140 at date XYZ, you should just buy a call at $135 strike expiring at XYZ. Doing a calendar spread helps you squeeze a little bit more money out of your trade perhaps, but incurs too much tax complications in my opinion to make it worth the headache.

And if you don’t satisfy the 4 criteria above, I most definitely wouldn’t recommend this strategy. It’s great that you’re here to read about advanced options strategies and all, but you’ll have a lot more money if you’d do something simple, like invest in the S&P 500.

0 Comments