In this post, I’ll give a summary of Andy Grove’s High Output Management book. I’ll also run through the key lessons I’ve learned from it.

In case you didn’t know – Andy Grove is a legend in the Silicon Valley. He almost single-handedly built the team required for Intel to dominant the CPU market, which in turn gave them enough traction to power PCs everywhere. Of all the innovations that came from the Silicon Valley, one could almost trace everything back to Andy Grove. From culture-building to running businesses to technological advancements, there’s almost no book that I can’t think of in recent memory that doesn’t at least reference Andy Grove once.

Off the top of my head, here are some books that refer to Andy Grove as a case study:

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things by Ben Horowitz

- Great By Choice by Jim Collins

- Measure What Matters by John Doerr

- The Road Less Stupid by Kevin J. Cunningham

The following are key lessons I’ve learned and my attempt at a summary of High Output Management. I highly encourage you to pick up your own copy as you’ll most definitely get lessons and learnings unique to you and your situation.

High Output Management In Summary: Managerial Leverage

The book’s called “High Output Management” because it teaches people how to be managers that create high output for the company they work for.

Managers have people reporting to them, and in that way, they have leverage.

- Example: 1 hour of manager-to-employee time can result in 25% more productive time for said employee for the next 40 hours. This is a high leverage activity.

But what’s an “output”? Simply put, it’s the results/outcome that the manager is supposed to deliver.

As such, a manager must take responsibility for the outcomes they’re assigned. They aren’t responsible for doing the things that supposedly will get the outcomes. They are responsible for the actual results.

In order to achieve actual results, a manager must have the proper information to make good decisions. In order to make decisions, managers should spend the most of their day gathering information. Information can be gathered through:

- Various internal meetings, including 1-on-1s

- Talking to clients

- Work-related water cooler chats

- Looking at and responding to relevant emails.

With good intel, a manager can then make a decision that is based on concrete information as opposed to speculation.

Once a manager knows what to do, the next thing is to get their reports to actually do it.

What’s A Manager’s Job, Anyway?

Throughout various meetings, a manager’s job is to influence and nudge those around them to do the right thing. In this way, a manager has tons of influence on the output of a company, both negative and positive.

If a manger does a good job and influences folks to do the right thing via appropriate nudging, the collective output of the folks they’ve influenced would be huge.

Conversely, a “depressed” and/or “waffling” manager will create almost infinitely negative leverage for the company. This is because anyone influenced by the manager will do almost no work, costing the company enormous sums of money.

Get High Output With Batching

Batching is waiting for a threshold of items before processing those items.

In the 4-Hour Workweek example, you’d generally wait for enough clothes before you do a load of laundry, because that’s the most efficient. You wouldn’t start doing a load of laundry where there’s only a pair of socks in your washing machine. This would waste a lot of water, money, time, and energy.

In the office example, this means turning something that’s fragmented and irregular into something regular. Take interruptions for example – one should batch random interruptions at work and process all those interruptions together in one time slot.

As an example, you might notify your colleagues that you have office hours. In those office hours, you’ll dedicate 100% of your attention to answering questions, emails, and just let yourself get completely interrupted.

This will help save your concentration and allow you to be more productive outside of those ‘distraction hours.’ For other strategies on improving your productivity so you can work less, and increase your effective hourly pay, read how to work less than 40 hours a week.

When you allow yourself to be interrupted constantly, you won’t be able to do high quality work. Our brains simply don’t work that way. And, as a manager of employees who do knowledge work, you should create an environment where your subordinates are able to conduct long periods of high-quality, concentrated work.

That is, you should do the exact opposite of what my manager does, which is:

- Don’t build a culture where you expect people to reply to emails within 2 hours.

- Do encourage minimizing attendance to meetings when it’s irrelevant your subordinates.

Now that you understand:

- What managerial leverage is,

- What a manager’s job is, and

- The importance of batching work to maximize output

Let’s talk about something else that has very high managerial output: training your subordinates.

High Output Management Summary On Training

A lot of modern culture is giving the employee autonomy. This is great, to a certain extent. A lot of times though, the attitude of “I’ll let them learn from their own mistakes!” is pure laziness, and costs the company a lot of money.

As Andy Grove says:

The problem with this is that the subordinate’s tuition is paid by his customers. And that is absolutely wrong. The responsibility for teaching the subordinate must be assumed by his supervisor…

In other words, training is required. Don’t be lazy and rip off your company’s customers by not training your employees properly.

Training is also an ultra-high leverage activity that a manger can do. In fact, the following passage from the book implies it is the highest leverage activity that a manager can perform:

Training is, quite simply, one of the highest-leverage activities a manager can perform. Consider for a moment the possibility of your putting on a series of four lectures for members of your department. Let’s count on three hours of preparation for each hour of course time—twelve hours of work in total. Say that you have ten students in your class. Next year they will work a total of about twenty thousand hours for your organization. If your training efforts result in a 1 percent improvement in your subordinates’ performance, your company will gain the equivalent of two hundred hours of work as the result of the expenditure of your twelve hours.

In summary, the book wants you to have high output management. What better way to provide high output by maximizing your time leverage so that your subordinates are as competent as possible?

Consider the opposite, which is my reality at my current place of employment. There’s no training at all. Everyone’s just expected “to know” stuff. The result: everyone’s completely incompetent and asks really basic questions. The time that could have been spent doing productive work is now filled with conversations about things that should have been covered in a basic curriculum.

But I digress.

Once you’ve got a training plan in place, please understand that training is an iterative and constant process.

Training is iterative because just as there’s no possible way you can write perfect code the first time around, there’s no way you can put together a training that’s perfect the first time around. The iterative process allows you to refine your training materials and come up with newer and better versions of it.

Training is a constant process because you can’t expect to train someone to do one subdomain of things once, and then expect them to be good forever. People have short memories and need refreshers. And more importantly, people need different types of training for the different types of work you’d expect them to do. Unless, of course, you expect your subordinate to be a one-trick pony (i.e. low output employee that can be automed).

High Output Management Summary: Measure Stuff

Now that you understand the importance of training and high managerial leverage, how do you know if you’re actually “managing” correctly?

That is, your training could suck and result in nothing. Likewise, grasping the concept of high-leverage doesn’t mean you’re actually doing it.

So how do you know?

One way to know how you’re doing is to measure what’s going on, empirically. Measurements help you see in concrete terms:

- What progress you’re making

- Early indicators of arising problems, so you have ample time to react to it

When coming up with metrics to measure stuff, you shouldn’t have only one set of measurements that’ll always bias you towards one set of actions.

For example, if you’d like to not run out inventory, you might measure your inventory levels. But if you only measure your inventory levels, the only action that it’ll skew you towards is to purchase new inventory. With only one measurement of inventory, you can easily overreact and frequently buy more inventory than you need (i.e. choking working capital and slowing / destroying your business growth).

Instead, you should have “counter”-measurements. In the inventory example, you ought to measure:

- Inventory levels to bias you towards the action of purchasing new stock if your stock is running low.

- Frequency of inventory shortages to give you clarity on how often you actually run out of stock. If the answer is “never,” you might be purchasing too much inventory. Frequency of actual inventory shortages will ground you and prevent you from overreacting for when the inventory levels are “dangerously” low. Dangerous is in quotes because it’s obviously not dangerous if you haven’t ran out of stock before.

In other words: measuring inventory levels bias you towards buying more inventory, and measuring frequency of inventory shortages bias you towards the opposite action: not buying more inventory.

Thus, you should always have your metrics/measurements in pairs so that action biases and cognitive biases are minimized.

1-on-1s (One On Ones) Are Important

Funny story: when I first began my career, I had 1-1s with my manager.

As I transitioned into new teams throughout my career I noticed one thing: my new managers never try to set up 1-1s, even after a few weeks working for the team. Inevitably, I’m the one that initiates the suggestions and sets up the weekly 1-1 meetings.

But why are 1-1s so important? They’re important because:

- They give clarity. A manager can “nudge” their subordinates to do the right thing to maximize their output. Maximizing their output = the subordinates can do well in their performance review = they get promoted = they satisfy their Maslow’s hierarchy needs for money and achievement = good employees stay. Clarity also lets the employee know exactly what benchmarks they need to hit to get a raise or a bonus. Conversely, the employee will know if they didn’t hit a target and therefore undeserving of incentives if they don’t hit it.

- They allow for frequent feedback. Frequent feedback to the employee allows them to course-correct so they don’t amplify their small mistakes. Frequent feedback allows the minimization of mistakes and maximization of productivity. This all again, boils down to allowing the subordinate to maximize output and to flourish as much as possible in the company.

- Allows for personalization. 1-1 conversations tend to be more direct, honest, and a better connection is built in these types of conversation than group conversations. As a manager, you’ll be able to understand the subtle problems the subordinate is facing. As an subordinate, you might feel more comfortable sharing private details about your personal life so you can get some leeway for your work, for example. This type of closer conversation allows for a better manager-to-subordinate relationship to be built by allowing for higher fidelity communication. Of course, the fidelity of the communication depends on how the manager and the subordinates run the 1-1s.

- Allows for problems to propagate quickly. As mentioned in my Who You Do Is What You Aresummary, you want to know problems as they arise. Your subordinate should report any small problems to you so you can see if it’s a problem to be addressed, or whether it can be safely ignored.

Without one-on-ones, you’re not doing your job as a manager, period. In summary, how’s your high output management of your employee going if you’re not even communicating with them on a regular basis?

High Output Management Summary On Disagreements

Disagreements slow things down.

As mentioned in the Who You Do Is What You Are summary, we’d like to “disagree and commit”; High Output Management shows us how to actually execute this in practice.

Being unable to make decisions is one of the worst show-stoppers in a business. In a situation where a decision is “stuck” and no agreement can be made, this is how a manager can assert their position:

“This is what I, as your boss, am instructing you to do. I understand that you do not see it my way. You may be right or I may be right. But I am not only empowered, I am required by the organization for which we both work to give you instructions, and this is what I want you to do…”

I personally think this wording strikes a great balance between being a tyrant and reasonable. On the one hand, you are asserting your power over your subordinate, which is tyrannical (but that comes with the territory of wage slavery – learn how to minimize this impact by working less than 40 hours/week).

On the other hand, the manager is explaining to the subordinate that they’ve got no choice. The organization needs to commit to a decision and execute it and move forward. Furthermore, the blow of asserting your power is made less insulting by admitting that the subordinate could be right.

This way of phrasing things is nice because it says “it’s not about being right; we just need to make forward progress so we can move onto the next thing.”

A Players vs. B Players

A-players are your best employees.

B-players are your mediocre ones.

Common management malpractice is to focus on ‘making the B-players better.’

The book disagrees with this, as I do. A-players are the talent, and so most of the adoration and attention should be given to them. More training to A-players yields significantly more leverage to the same training to B-players.

Giving more money to A-players (and thereby motivating them) yields better results for the company than doing the same for B-players.

Average people are average. They can be made better, but with extraordinary effort on your part.

A-players are A-players. They can be made better without too much effort, as they’re self-motivated.

If you’ve got a group of people that haven’t demonstrated outlier performance vs. a smaller group of people that have, why not just focus on the smaller, elite group as opposed to wasting your time with the useless masses?

Focus on your A-players to get more results, with the lowest amount of effort.

In Summary

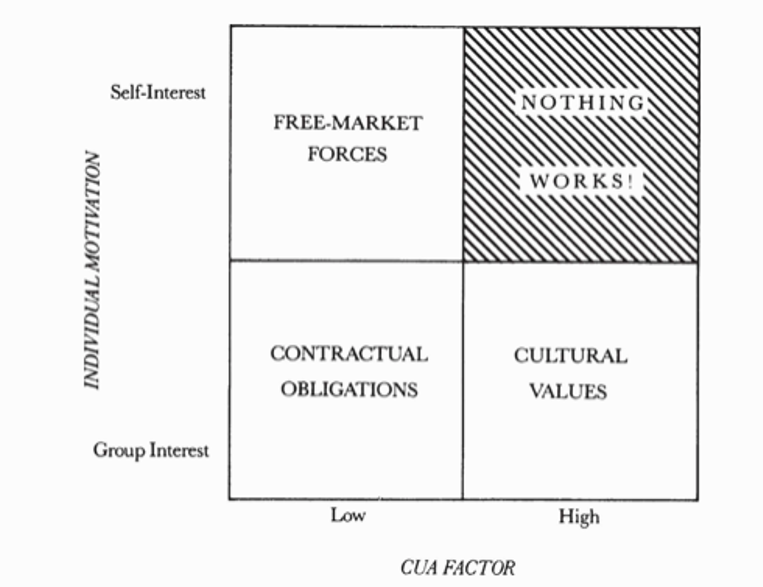

I want to end with Andy Grove’s “CUA” chart. “CUA” is just basically how complex a job is. And the grid is broken down like this:

The chart reads like this:

- “Someone with self-interest can thrive in a low complexity environment by motivating them with free-market forces.” Think of someone who is happy with a high-enough paying job where things are easy enough to do. But they might jump to another gig if they offer more money or an easier job for the same pay.

- “Someone that works a low complexity job and is motivated by the group’s success can be driven to work via obligations.” Think of someone who stops at a red-light even if there’s no cameras or cars around. It’s just a contractual obligation to do so.

- “Someone motivated by group interest in a very complex environment can be driven to work with cultural values.” Think of someone working at a mission-oriented startup that’s extremely complex. Him/her and their coworkers work together in a very complex environment, not because of good pay (free-market forces) or obligations, but because they believe in the mission and love the culture.

- “Someone with self interest working in a high complexity environment will quit and find a job that’s easier.”

A naïve reading of this chart would end up with the interpretation: “Then I should just hire people with group interest in mind.” This is wrong.

First, you can’t guarantee everyone permanently has group interest in mind. Second, people can fake group interest quite easily. Ergo, trying to hire only people motivated by group interest isn’t feasible, and at worse, perverse. Think about it: most people will have self-interest in mind, and a lot of people with self-interest in mind are very smart. Why cut your workforce down to a narrow group of people with only group interest in mind? Hiring people with only group interest in mind is literally hiring against human nature, which is perverse.

So what should you do instead?

Instead, you should make your organization’s CUA factor as low as possible so it can be compatible with employees, regardless of whether or not they’re primarily motivated by self-interest or group interest.

But how can you lower your org’s CUA?

Simple: just follow the High Output Management summary points above.

As a concrete example: I have self-interest and the CUA factor of my work is very high. Thus, nothing really works on me. No managerial tactics or some BS “getting to know you meeting,” or some stupid org-wide, shallow tactic will make me like the company. However, the CUA factor is high because it’s artificially high. The job itself is quite simple, but is made very complicated by politics. If my work had no politics, I’d classify the CUA factor as very low, and I’d only be motivated by free-market forces. This means I’d only switch jobs if someone offered me a much higher paying job, or a job with significantly lower CUA (but if there was no politics, then it’s very hard to have a much lower CUA).

Thus, even a selfish bastard like me can be retained permanently if CUA is low enough, because it’s very hard for a competitor company to either: 1) pay a lot more than market rate, or 2) establish and prove that they have such a low CUA that it’d be motivating for me to move.

But as it stands, the CUA is so high I’d move companies if the wind blows the right way.

Final score: 8/10. Great book. Practical. But a very dry read and not entertaining.

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks